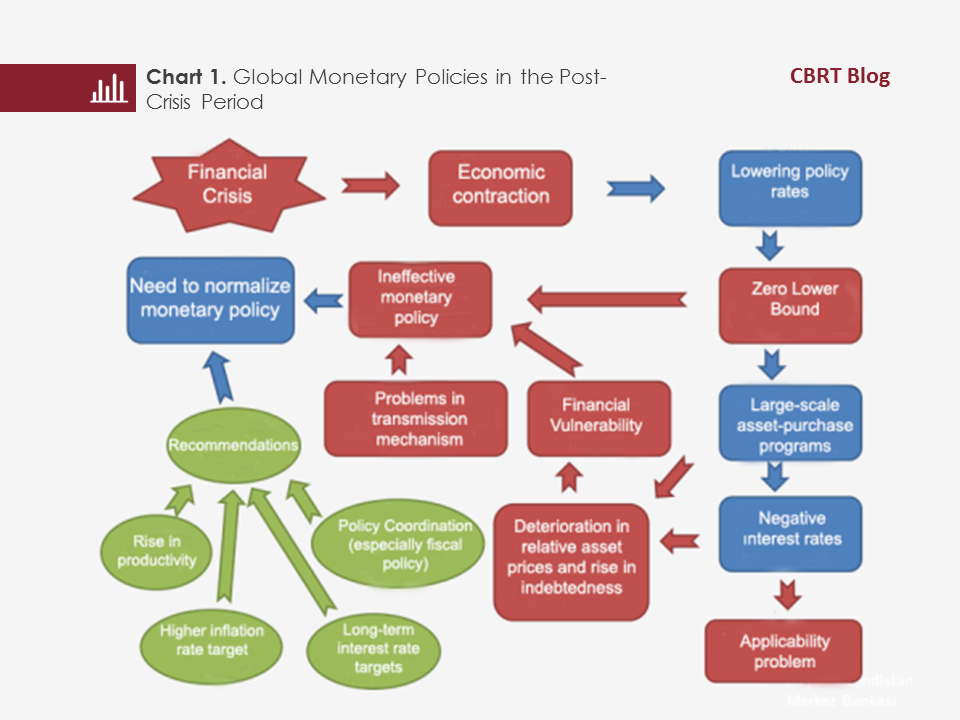

The monetary policies, which were unconventionally eased by advanced economies after the global financial crisis, fell short of being successful in attaining inflation targets and returning to full employment and it was also discovered that they could lead to potential problems with respect to the operation of the financial system. In this post, we will try to evaluate the performances of the recent global monetary policies and alternative implementations that can be introduced in the future with respect to the four questions below.

1. Is the transmission mechanism operational?

Central banks are aiming to revive economic activity by bringing down interest rates close to zero or even to negative territory or increasing liquidity with asset purchasing programs. As summarized by Hannoun (2015), the impact of these efforts is expected to be observed through several channels such as credits, asset prices, reflation and exchange rates.

Certainly, the most important of these channels is the “credit” channel. In a low-interest rate environment, the aim is to bring down loan rates by decreasing the funding costs of banks and to encourage economic units to consume and invest via borrowing. Nevertheless, recently, it is not possible to say that this channel has been working flawlessly. In post-crisis periods, consumers may be reluctant to spend money via borrowing due to the decline in job security or the low real interest rates. Moreover, as stated in Krugman (2013) and in OECD (2014), the deterioration in income distribution is an important factor suppressing consumer demand. With respect to investment, according to Stiglitz (2016), the capacity utilization rate is already low amid weak global demand and therefore, decreasing interest rates falls short of stimulating new investments. Moreover, banks keep credit conditions tight as they have been unable to fully repair their crisis-torn balance sheets. Meanwhile, the fact that the decline in short-term interest rates cannot be fully applied to deposit rates that are the primary source of funding of loans, is one of the factors limiting the decline in loan rates through the cost channel. For other channels cited above, we can talk about weaker and one-off effects or implementation difficulties.

In a nutshell, the experiences reveal that the unconventional monetary policies have fallen short of generating the desired results due to flaws in the monetary transmission mechanism and/or structural problems. Nevertheless, it would not be fair to say that these policies are completely ineffective. Several studies in academia claim that the current growth and inflation outlook would have been worse if these policies had not been implemented (Peersman, 2011; Gambacorta et al., 2012, Santor and Suchanek, 2016).

2. Can the monetary policy be implemented effectively in case of a new economic contraction?

This question can be answered in the framework of two primary problems. First problem is the issues pertaining to the monetary transmission mechanism mentioned above. These problems indicate that it would be helpful to support the monetary policy with other policies to ensure operability or enhance the impact of the monetary policy. The second problem is that the current level of interest rates is too low. When policy rates are low, it would be difficult to ease the policy further in the face of a new economic contraction. In this case, central banks would either employ non-interest methods like asset purchases or bring down the policy rate further, below zero. Nevertheless, as it will be summarized in the following section, such policies contain some risks if they have been used for a long time. Here, the core problem is that banks cannot reflect these policies onto deposit rates. Applying negative interest rates for deposit accounts may lead to withdrawals from accounts and cash may go under the mattress. The reason for this is that keeping cash means zero interest, which means its yield is higher than keeping the money in a deposit account. Nevertheless, Goodfriend (2016) and Kimball (2015) claim that the “flight to cash” problem can be overcome by implementations like the carry tax and that negative interest rates can in fact be applied. The social reaction to the introduction of carry tax and its applicability are disputable on the other hand. The problems pertaining to unconventional policies seem likely to weaken the effectiveness of the monetary policy in case of a new contraction cycle.

3. What are the risks posed by close-to-zero or negative interest rates and large-scale asset purchases?

As mentioned above, one the objectives of low interest rates is encouraging borrowing. Nevertheless, prolonged low-interest periods and excessive debt accumulation may become a risk factor. Periods of excessively easy borrowing may lead to excessive increase in both public and private sector indebtedness. If the resources attained via borrowing are not used effectively, they are likely to instigate new balance sheet crises in the future. Moreover, easy borrowing can trivialize concepts such as debt management and risk analysis that are crucial for financial stability.

The returns of financial assets in the markets go in tandem with the risks they are associated with. In other words, it is natural that the asset returns of Germany and Italy are different. When low or negative interest rates become permanent, investors start to move towards more risky assets rather than risk-free assets with negative interest rates, and the above-mentioned difference decreases. This situation damages market process by increasing the risk that investors bear. Similarly, broad-based asset purchases influence relative asset prices in the market and undermine market operation.

Possibility of bubbles in asset prices is also considered as a risk factor. Asset prices climb as interest rates fall. Nevertheless, some asset prices may experience sudden drops if interest rates return to normal or expectations arise for a likely normalization of interest rates. Investors, who have largely invested in such assets, might be adversely affected by sudden price changes and this could even lead to a financial crisis.

4. What are alternative suggestions?

Central banks face two options. First, to continue to purchase assets and implement negative interest rates; second, to get rid of the low or negative interest rate issue by finding a way to rapidly increase the policy rate. Admitting that the first option is less preferred due to the risks associated with it, the option left is alternative policies that would support normalization in interest rates.

One of the suggestions to this end can be setting a higher inflation rate for central banks. A higher inflation target would push nominal interest rates up and make the monetary policy effective again. However, it should be borne in mind that such a move can damage the long-sought central bank credibility and higher inflation can create relative price effects.

Structural reforms to be introduced towards increasing productivity that had fallen after the crisis could support growth and help increase interest rates. However, such policies could adversely affect growth through costs, particularly in the short term (Summers, 2015). Moreover, Vogel (2014) states that these costs can climb higher if the interest rates are closer to zero.

The Bank of Japan’s recent policy stance targeting long-term interest rates can be another alternative. However, it would be wise to wait for some time to evaluate the success of this policy. Meanwhile, Krugman (2012) points out that the success of a long-term interest rate target is highly dependent on credibility, just like exchange rate targets.

The most reasonable recommendation among those offered to bring interest rates to normal levels seems to be the one that suggests supporting growth via fiscal policy. The new government after the US presidential elections will likely pursue a policy in line with this. Recently, the European Commission, too, has called on the euro area to use fiscal policy. Two measures come to the fore with respect to the effectiveness of fiscal policy. The first one is the low growth environment. Empirical studies indicate that fiscal policies can be more effective in an environment of low growth. In this respect, the current conditions seem to be favorable for fiscal policy. The second important factor is the fiscal position, or how much room the fiscal policy has for maneuver. When a country’s fiscal position is not strong enough, there is a risk that the expansionary fiscal policy will adversely affect economy, frustrating the expectations.

To conclude, it is observed that central banks are willing to normalize their policies. Nevertheless, growth and employment developments worldwide, except for the USA, are not favorable enough to allow normalization at the moment. Each recommended solution brings its own risks. Accordingly, short and long-term outlook of global monetary policy still remain uncertain.

Bibliography:

Agostini G, Garcia JP, Gonzales A, Jia J, Muller L and Zaidi A (2016), “Comparative Study of Central Bank Quantitative Easing Programs”, Report School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) Columbia University.

Gambacorta L, Hoffman B and Peersman G (2012), “The Effectiveness of Unconventional Monetary Policy at the Zero Lower Bound: A Cross-Country Analysis”, BIS Working Paper No:384.

Goodfriend, M (2016), “The case for unencumbering interest rate policy at the zero lower bound”, Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Paper, Wyoming, 26-27 August.

Hannoun, H (2015), “Ultra-low or negative interest rates: What they mean for financial stability and growth”, Remarks at Eurofi High-Level Seminar, Riga, 22 April.

Kimball, M (2015), “Negative Interest Rate Policy as Conventional Monetary Policy”, National Institute Economic Review (234:1)

Krugman, P (2012), “Targets, Instruments, and the Zero Bound (Wonks Only)”, New York Times,31 March.

Krugman, P (2013), “Why Inequality Matters”, New York Times,15 December.

OECD (2014), “Focus on Inequality and Growth”, December 2014.

Peersman, G (2011), “Macroeconomic Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy in the Euro Area”, ECB Working Paper Series No:1397.

Santor E and Suchanek L (2016), “A New Era of Central Banking: Unconventional Monetary Policies”, Bank of Canada Review 2016 (Spring) pages 29-42.

Stiglitz, J (2016), “The problem with negative interest rates", The Guardian, 18 April.

Summers L, (2015), “Reflections on Secular Stagnation”, Remarks at Public Policy & Finance, Princeton University’s Julius-Rabinowitz Center, February.

Vogel L (2014), “Structural reforms at the zero bound”, European Comission Economic Papers 537, November.